Kobe Bryant: Orthopaedic Surgeon Discusses Star's Achilles Tendon, Knee Injuries

Published by Daniel Lewis on August 7, 2014 at Bleacher Report. Click to read article on Bleacher Report.

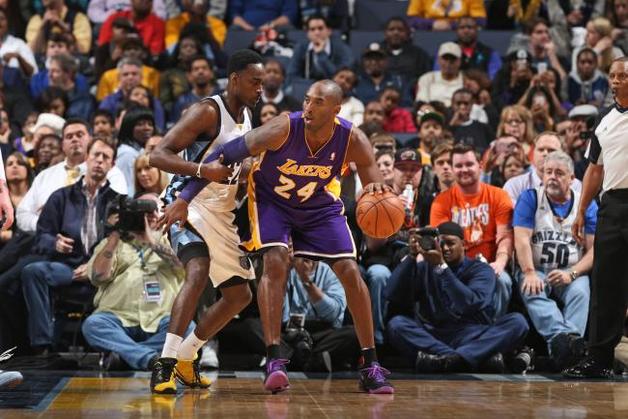

Ron Powell/Getty Images

Ron Powell/Getty Images

In a one-on-one interview with David Geier, MD, an orthopaedic surgeon and sports medicine specialist, Dr. Geier and sports journalist Daniel Lewis discuss Kobe Bryant’s Achilles tendon and knee injuries, and his attempt to recover and return to the court at age 36.

It was April 12, 2013—the Los Angeles Lakers were playing the Golden State Warriors in L.A.’s third-to-last game of the season. With a playoff berth hanging in the balance, Kobe Bryant had played the entire game, despite having hyperextended his left knee early in the third quarter.

Only three minutes in the fourth quarter remained when Bryant made a seemingly routine move, pushing off his left foot in an attempt to drive around the tightly defending Harrison Barnes. At that moment, Bryant felt a pop before crumpling to the ground, and the referee called a foul.

Grabbing the back of his left ankle as he grimaced, he knew he had torn his Achilles tendon.

“I was just hoping it wasn’t what I knew it was,” Bryant said, per Arash Markazi of ESPNLosAngeles.com. “I tried to walk it off hoping that the sensation would come back but no such luck.”

Kobe limped back to hit his two free throws before heading off to the locker room and an offseason of rehabilitation. L.A. ended up holding on to win 118-116. Propped up on crutches after the game, Bryant was visibly emotional, knowing he faced a tall mountain to climb.

"I was really tired, man. I was just tired in the locker room. Upset and dejected and thinking about this mountain I have to overcome. This is a long process. I wasn’t sure I could do it. But then the kids walked in here, and I had to set an example. ‘Daddy’s going to be fine. I’m going to do it.’ I’m going to work hard and go from there."

Kobe returned for a mere glimpse during the 2013-2014 season before suffering a season-ending knee injury, so it remains uncertain if he has scaled the mountain that is his torn Achilles tendon. He logged just 177 minutes in six games, averaging 13.8 points, 6.3 assists and 5.7 turnovers.

The Achilles tendon, or calcaneal tendon, mainly connects the calf muscles—gastrocnemius and soleus—to the calcaneus, or heel bone. It is the strongest and thickest tendon in the human body. The tendon and calf muscles work together to enable a person not only to play basketball, but also to perform everyday activities such as jumping, running and climbing stairs.

Kobe suffered a third-degree tear in that his tendon had completely ruptured, meaning he would face a lengthy rehabilitation process. A number of professional athletes, including NBA greats Isiah Thomas and Shaquille O’Neal, have retired early due to a torn Achilles tendon.

“It’s a very difficult injury in professional athletes,” says Dr. David Geier, an orthopaedic surgeon and former director of sports medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina. “It can take up to a year to get back full speed and explosive power—jumping ability, push-off ability and the first step, which in a basketball player is so important.

“There was a study that came out last year about Achilles tendon ruptures in NBA players, and only a few of the players got back to playing at the same level.”

That study would be the one spearheaded by Dr. Douglas Cerynik and Dr. Nirav Amin, both orthopedic surgeons of Drexel University. They examined 18 NBA players who tore an Achilles tendon between 1992 and 2012. Of those players, seven never set foot again on an NBA court. Three players returned for one year, and eight players came back for multiple seasons.

The average age and years of NBA experience for the players in the study was 29.7 and seven, respectively. These numbers are dwarfed by those of Bryant, who at age 36 has played 18 seasons in the NBA. He is clearly at the wrong end of the aging curve.

“In that study, they were a lot younger,” said Geier. “In the NBA, you do not usually get up to his age, and there are not that many players who make it to that point in their career like he has. His odds are not great, but that doesn’t mean that he can’t do it for sure. It’s just that it’s very challenging. And we don’t know because he didn’t get back for very long at all.”

In their first year returning from injury, the 11 players played 5.21 fewer minutes per game and posted a player efficiency rating (PER) that was 4.64 lower than their pre-injury PER.

The sole player who returned to form was Dominique Wilkins, who came back at age 32 to average 29.9 points per game. Wilkins, though, had played 27,482 minutes over 10 NBA seasons when he suffered the injury. In contrast, Kobe has logged an Iron Man-like 54,041 minutes. Despite being just two years older than Wilkins at the time of his injury, Bryant has unbelievably spent nearly twice as much time on the NBA hardwood.

While the study does not paint a promising picture for Bryant, it is worth noting that its conclusions are based on a small sample size. After all, compiling such data is more difficult in basketball because the NBA lacks a centralized injury database like that of the NFL.

“Can a player who works really hard on the rehab come back?” Geier reflected. “Absolutely, but it takes a lot of time. It is not something from which they often come back to play at the same level. They may be a step slower or lose an inch or two on their vertical.”

Since the Achilles tendon plays such a key role in generating power in the lower leg, a ruptured Achilles is bad news for any athlete and even worse news for a superstar such as Bryant.

It was April 12, 2013—the Los Angeles Lakers were playing the Golden State Warriors in L.A.’s third-to-last game of the season. With a playoff berth hanging in the balance, Kobe Bryant had played the entire game, despite having hyperextended his left knee early in the third quarter.

Only three minutes in the fourth quarter remained when Bryant made a seemingly routine move, pushing off his left foot in an attempt to drive around the tightly defending Harrison Barnes. At that moment, Bryant felt a pop before crumpling to the ground, and the referee called a foul.

Grabbing the back of his left ankle as he grimaced, he knew he had torn his Achilles tendon.

“I was just hoping it wasn’t what I knew it was,” Bryant said, per Arash Markazi of ESPNLosAngeles.com. “I tried to walk it off hoping that the sensation would come back but no such luck.”

Kobe limped back to hit his two free throws before heading off to the locker room and an offseason of rehabilitation. L.A. ended up holding on to win 118-116. Propped up on crutches after the game, Bryant was visibly emotional, knowing he faced a tall mountain to climb.

"I was really tired, man. I was just tired in the locker room. Upset and dejected and thinking about this mountain I have to overcome. This is a long process. I wasn’t sure I could do it. But then the kids walked in here, and I had to set an example. ‘Daddy’s going to be fine. I’m going to do it.’ I’m going to work hard and go from there."

Kobe returned for a mere glimpse during the 2013-2014 season before suffering a season-ending knee injury, so it remains uncertain if he has scaled the mountain that is his torn Achilles tendon. He logged just 177 minutes in six games, averaging 13.8 points, 6.3 assists and 5.7 turnovers.

The Achilles tendon, or calcaneal tendon, mainly connects the calf muscles—gastrocnemius and soleus—to the calcaneus, or heel bone. It is the strongest and thickest tendon in the human body. The tendon and calf muscles work together to enable a person not only to play basketball, but also to perform everyday activities such as jumping, running and climbing stairs.

Kobe suffered a third-degree tear in that his tendon had completely ruptured, meaning he would face a lengthy rehabilitation process. A number of professional athletes, including NBA greats Isiah Thomas and Shaquille O’Neal, have retired early due to a torn Achilles tendon.

“It’s a very difficult injury in professional athletes,” says Dr. David Geier, an orthopaedic surgeon and former director of sports medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina. “It can take up to a year to get back full speed and explosive power—jumping ability, push-off ability and the first step, which in a basketball player is so important.

“There was a study that came out last year about Achilles tendon ruptures in NBA players, and only a few of the players got back to playing at the same level.”

That study would be the one spearheaded by Dr. Douglas Cerynik and Dr. Nirav Amin, both orthopedic surgeons of Drexel University. They examined 18 NBA players who tore an Achilles tendon between 1992 and 2012. Of those players, seven never set foot again on an NBA court. Three players returned for one year, and eight players came back for multiple seasons.

The average age and years of NBA experience for the players in the study was 29.7 and seven, respectively. These numbers are dwarfed by those of Bryant, who at age 36 has played 18 seasons in the NBA. He is clearly at the wrong end of the aging curve.

“In that study, they were a lot younger,” said Geier. “In the NBA, you do not usually get up to his age, and there are not that many players who make it to that point in their career like he has. His odds are not great, but that doesn’t mean that he can’t do it for sure. It’s just that it’s very challenging. And we don’t know because he didn’t get back for very long at all.”

In their first year returning from injury, the 11 players played 5.21 fewer minutes per game and posted a player efficiency rating (PER) that was 4.64 lower than their pre-injury PER.

The sole player who returned to form was Dominique Wilkins, who came back at age 32 to average 29.9 points per game. Wilkins, though, had played 27,482 minutes over 10 NBA seasons when he suffered the injury. In contrast, Kobe has logged an Iron Man-like 54,041 minutes. Despite being just two years older than Wilkins at the time of his injury, Bryant has unbelievably spent nearly twice as much time on the NBA hardwood.

While the study does not paint a promising picture for Bryant, it is worth noting that its conclusions are based on a small sample size. After all, compiling such data is more difficult in basketball because the NBA lacks a centralized injury database like that of the NFL.

“Can a player who works really hard on the rehab come back?” Geier reflected. “Absolutely, but it takes a lot of time. It is not something from which they often come back to play at the same level. They may be a step slower or lose an inch or two on their vertical.”

Since the Achilles tendon plays such a key role in generating power in the lower leg, a ruptured Achilles is bad news for any athlete and even worse news for a superstar such as Bryant.

Andrew D. Bernstein/Getty Images

Andrew D. Bernstein/Getty Images

What caused Kobe’s Achilles tendon to rupture? Age was likely a factor, as tendons and ligaments typically lose water as they age, making them less elastic and thus more fragile.

An obvious additional factor may have been overuse, as Kobe had been playing a heavy dose of minutes throughout the season and even more so leading up to the injury. In 2012-2013, the veteran Laker was second overall in playing time at 38.6 minutes per game and had averaged an astounding 45.2 minutes in the six games during the month he suffered the injury.

With the team desperately clinging to a playoff spot at the time, many believe that Bryant’s injury was the direct result of then-head coach Mike D’Antoni’s unwillingness or inability to set aside any significant minutes for Bryant to rest. However, this simple connecting of the dots is a tenuous argument at best because Achilles tendon tears are typically freak injuries.

“I wrote a newspaper column about it at the time about how D’Antoni was taking all that criticism," said Geier. "Could the fact that he played too many minutes contribute to the injury? Sure. But there is no absolute right answer because Achilles tendon ruptures can occur without overuse.

“A good example is the 2011 NFL training camp and preseason, when there was a rash of Achilles tendon ruptures. I think there was 10 in just a few weeks. That you wouldn’t think is overuse because they had just returned to the field after a lockout that had kept them fresh.”

Kobe Suffers a Knee Injury

After a grueling eight months of post-surgical rehabilitation, Bryant made his much-anticipated return to the court on December 8 in a home game against the Toronto Raptors.

Just five games later, on December 17, Bryant was posting up the Memphis Grizzlies’ Tony Allen when he took an awkward step, twisted and hyperextended his left knee. Kobe fell to the ground and writhed in pain. It was a sight all too familiar, except this time he grabbed his knee.

An MRI later showed that he had suffered a fracture of the lateral tibial plateau in his left knee.

The tibia is the larger of the two bones in the lower leg. Unlike the much smaller fibula, the tibia bears the majority of an individual’s body weight. The top portion of the tibia widens to form a surface known as the tibial plateau, which serves as the base of the knee joint.

The tibial plateau is composed of trabecular bone, which is softer than the thicker bone in the lower tibia. A tibial plateau fracture is an uncommon injury that usually occurs after a collision or fall. It is often seen in auto-pedestrian accidents, giving it the nickname “bumper fracture.”

“It is something that can often result from a direct blow or a very sudden impact landing that has nothing to do with prior injury,” Geier said.

In most cases, the tibial plateau sustains a fracture when significant force is placed on the femur, driving it into the softer trabecular bone of the tibial plateau. Indirect trauma can also cause the fracture if it is accompanied by excessive torsion.

An obvious additional factor may have been overuse, as Kobe had been playing a heavy dose of minutes throughout the season and even more so leading up to the injury. In 2012-2013, the veteran Laker was second overall in playing time at 38.6 minutes per game and had averaged an astounding 45.2 minutes in the six games during the month he suffered the injury.

With the team desperately clinging to a playoff spot at the time, many believe that Bryant’s injury was the direct result of then-head coach Mike D’Antoni’s unwillingness or inability to set aside any significant minutes for Bryant to rest. However, this simple connecting of the dots is a tenuous argument at best because Achilles tendon tears are typically freak injuries.

“I wrote a newspaper column about it at the time about how D’Antoni was taking all that criticism," said Geier. "Could the fact that he played too many minutes contribute to the injury? Sure. But there is no absolute right answer because Achilles tendon ruptures can occur without overuse.

“A good example is the 2011 NFL training camp and preseason, when there was a rash of Achilles tendon ruptures. I think there was 10 in just a few weeks. That you wouldn’t think is overuse because they had just returned to the field after a lockout that had kept them fresh.”

Kobe Suffers a Knee Injury

After a grueling eight months of post-surgical rehabilitation, Bryant made his much-anticipated return to the court on December 8 in a home game against the Toronto Raptors.

Just five games later, on December 17, Bryant was posting up the Memphis Grizzlies’ Tony Allen when he took an awkward step, twisted and hyperextended his left knee. Kobe fell to the ground and writhed in pain. It was a sight all too familiar, except this time he grabbed his knee.

An MRI later showed that he had suffered a fracture of the lateral tibial plateau in his left knee.

The tibia is the larger of the two bones in the lower leg. Unlike the much smaller fibula, the tibia bears the majority of an individual’s body weight. The top portion of the tibia widens to form a surface known as the tibial plateau, which serves as the base of the knee joint.

The tibial plateau is composed of trabecular bone, which is softer than the thicker bone in the lower tibia. A tibial plateau fracture is an uncommon injury that usually occurs after a collision or fall. It is often seen in auto-pedestrian accidents, giving it the nickname “bumper fracture.”

“It is something that can often result from a direct blow or a very sudden impact landing that has nothing to do with prior injury,” Geier said.

In most cases, the tibial plateau sustains a fracture when significant force is placed on the femur, driving it into the softer trabecular bone of the tibial plateau. Indirect trauma can also cause the fracture if it is accompanied by excessive torsion.

Joe Murphy/Getty Images

Joe Murphy/Getty Images

Even a season later, it is still unclear how exactly Bryant suffered the injury. The tibial plateau may have hit the floor, or the twisting stress he felt as he fell may have put stress on the bone.

Depending on the severity, a tibial plateau fracture can range from a less severe form that can be visualized only on an MRI scan to a more severe form in which the bone has fractured into many fragments. The more complex the fracture, the longer the recovery time.

Fortunately for Kobe, the fracture was non-displaced and confined to the lateral side of his tibial plateau. He avoided surgery as well as any significant soft tissue or meniscal damage.

Shortly after the injury, the Lakers announced Kobe would be sidelined for at least six weeks. Then, in late January, the team declared he would remain out through the All-Star break because of continued pain and swelling. As the All-Star break passed, the Lakers again postponed Bryant’s potential return to mid-March, before finally giving up on an in-season return on March 12 after a re-examination found the bone had still failed to heal.

In retrospect, it is not surprising Kobe’s recovery required much more than six weeks. Sufficient time is needed for the bone to heal properly and align itself. In the past, NBA players such as Yao Ming and Lorenzen Wright have sustained the same kind of injury and missed more than six weeks. In fact, Wright was only able to come back after nearly 10 weeks and 33 missed games, and Yao remained on the sidelines for 10 weeks, returning after a 32-game absence.

Since Bryant sustained the knee injury on the same leg as his ruptured Achilles tendon, many have wondered whether the first injury caused the second one. The answer is maybe.

“It’s not unreasonable to think that just in general with athletes that if you’re recovering from one injury, the muscles around that joint in the rest of that lower extremity still haven’t fully recovered, and so you’re subject to another injury,” said Geier.

In fact, Kobe’s left calf muscles appeared to show some atrophy during his brief return. If his calf lacked its usual strength, it may have been a factor in causing the fracture.

During motion, contraction of the gastrocnemius slows the tibia down and maintains flexion tension on the knee as it extends. As a result, an athlete faces a higher risk of knee hyperextension with atrophy of the calf muscles because they are unable to decelerate the tibia adequately enough. If the fracture occurred when Bryant’s knee hyperextended, then his possibly weakened calf muscles may have been the culprit.

“Maybe he did not have his full strength back in his calf muscles, his quads or his hamstrings, causing more stress to go to bone,” Geier stated. “It’s certainly possible.

“It is a little unusual to see a tibial plateau fracture in somebody so young without some sort of bone issue. The counterargument would be that that it’s typically a traumatic injury. Really, it’s one that could have been related to his torn Achilles tendon, or it could have occurred even if he had not suffered the Achilles tendon injury.”

Kobe's Orthokine Procedures

Having spent half of his lifetime running up and down an NBA hardwood floor, it is not all that surprising that Bryant has degenerative knee issues. Still playing at age 36, he has worked as hard as anyone to stave off Father Time using techniques such as diet, exercise and training.

Kobe also takes care of himself and manages his injuries by receiving Orthokine, a procedure developed by Dr. Peter Wehling, a German orthopaedist. Dating back to 2011, it seems as though every fall, Kobe makes his annual pilgrimage to Germany for the treatment.

Commonly referred to as “the Kobe procedure” or by its generic name “autologous conditioned serum,” Orthokine involves drawing blood out of Bryant’s arm, mixing it with various substances and then injecting it into his knee. The blood is drawn in the USA and then shipped frozen to Germany.

“The theory behind it has had more excitement than the studies and the results,” Geier acknowledged. “It is used for a lot of degenerative issues, such as tennis elbow, patellar tendon injuries and Achilles tendon problems. It is also being used for wear and tear of the articular cartilage of joints such as the knee or ankle—essentially early arthritis changes.”

The therapy is predicated on the activity of Interleukin-1 (IL-1). IL-1 is a protein that stimulates the immune system to combat infections, but it can also activate inflammatory cascades that can cause joint degeneration and cartilage destruction. In fact, it is known to play an integral role in joint diseases such as osteoarthritis and intervertebral disc degeneration.

The body also contains a protein called Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA), which inhibits the effects of IL-1. IL-1RA is produced by white blood cells and prevents IL-1 from binding to its receptor, thus reducing the inflammatory effects of IL-1. As part of the Orthokine treatment, IL-1RA is added to the plasma solution that is eventually infused into Kobe’s knee.

The treatment is actually different from platelet-rich plasma (PRP) therapy, a more common procedure. In PRP, the physician obtains a sample of patient blood before spinning it in a centrifuge. This centrifugation separates out a layer containing platelet-rich plasma and various activating factors, both of which are then injected together in their unadulterated form into the area of injury. It is believed that PRP accelerates the healing process.

A long list of athletes have received Orthokine, PRP or a similar treatment. Aside from Bryant, Peyton Manning, Tracy McGrady, Alex Rodriguez, and Tiger Woods are among hundreds of professional athletes who have undergone the procedure.

Neither PRP nor Orthokine are banned by the United States Anti-Doping Agency or the World Anti-Doping Agency. Moreover, Orthokine is not illegal, nor does it involve steroids, human growth hormone or other performance-enhancing substances.

Kobe believes the treatment works for him, but has it been proven effective in medical studies?

“The studies have not been terribly encouraging,” Geier noted. “Some patients tend to get some relief, whereas others do not seem to get much at all. We still think that there is a lot of hope, but there is a lot of work to do to figure out the right formulation.”

A study funded by Wehling found that Orthokine was effective in 67 percent of patients, comparing favorably to those receiving hyaluronic acid (32 percent) or placebo (33 percent). Other studies, though, either paint an incomplete picture or have been questioned by physicians.

Overall, anecdotal results are positive, but medical evidence is lacking. At worst, evidence has yet to suggest the treatment is associated with any immediate or long-term complications.

“There is not much of a downside other than the cost and the fact that it might not work,” Geier believes. “It is certainly better for a lot of things than are cortisone injections, but it is not by any means proven to be a foolproof, cure-all type of procedure.”

Ultimately, if Kobe wants it, then Kobe gets it. The future of the franchise rests on the health of their $48.5 million man, and so the Lakers will support anything that he believes will help.

Depending on the severity, a tibial plateau fracture can range from a less severe form that can be visualized only on an MRI scan to a more severe form in which the bone has fractured into many fragments. The more complex the fracture, the longer the recovery time.

Fortunately for Kobe, the fracture was non-displaced and confined to the lateral side of his tibial plateau. He avoided surgery as well as any significant soft tissue or meniscal damage.

Shortly after the injury, the Lakers announced Kobe would be sidelined for at least six weeks. Then, in late January, the team declared he would remain out through the All-Star break because of continued pain and swelling. As the All-Star break passed, the Lakers again postponed Bryant’s potential return to mid-March, before finally giving up on an in-season return on March 12 after a re-examination found the bone had still failed to heal.

In retrospect, it is not surprising Kobe’s recovery required much more than six weeks. Sufficient time is needed for the bone to heal properly and align itself. In the past, NBA players such as Yao Ming and Lorenzen Wright have sustained the same kind of injury and missed more than six weeks. In fact, Wright was only able to come back after nearly 10 weeks and 33 missed games, and Yao remained on the sidelines for 10 weeks, returning after a 32-game absence.

Since Bryant sustained the knee injury on the same leg as his ruptured Achilles tendon, many have wondered whether the first injury caused the second one. The answer is maybe.

“It’s not unreasonable to think that just in general with athletes that if you’re recovering from one injury, the muscles around that joint in the rest of that lower extremity still haven’t fully recovered, and so you’re subject to another injury,” said Geier.

In fact, Kobe’s left calf muscles appeared to show some atrophy during his brief return. If his calf lacked its usual strength, it may have been a factor in causing the fracture.

During motion, contraction of the gastrocnemius slows the tibia down and maintains flexion tension on the knee as it extends. As a result, an athlete faces a higher risk of knee hyperextension with atrophy of the calf muscles because they are unable to decelerate the tibia adequately enough. If the fracture occurred when Bryant’s knee hyperextended, then his possibly weakened calf muscles may have been the culprit.

“Maybe he did not have his full strength back in his calf muscles, his quads or his hamstrings, causing more stress to go to bone,” Geier stated. “It’s certainly possible.

“It is a little unusual to see a tibial plateau fracture in somebody so young without some sort of bone issue. The counterargument would be that that it’s typically a traumatic injury. Really, it’s one that could have been related to his torn Achilles tendon, or it could have occurred even if he had not suffered the Achilles tendon injury.”

Kobe's Orthokine Procedures

Having spent half of his lifetime running up and down an NBA hardwood floor, it is not all that surprising that Bryant has degenerative knee issues. Still playing at age 36, he has worked as hard as anyone to stave off Father Time using techniques such as diet, exercise and training.

Kobe also takes care of himself and manages his injuries by receiving Orthokine, a procedure developed by Dr. Peter Wehling, a German orthopaedist. Dating back to 2011, it seems as though every fall, Kobe makes his annual pilgrimage to Germany for the treatment.

Commonly referred to as “the Kobe procedure” or by its generic name “autologous conditioned serum,” Orthokine involves drawing blood out of Bryant’s arm, mixing it with various substances and then injecting it into his knee. The blood is drawn in the USA and then shipped frozen to Germany.

“The theory behind it has had more excitement than the studies and the results,” Geier acknowledged. “It is used for a lot of degenerative issues, such as tennis elbow, patellar tendon injuries and Achilles tendon problems. It is also being used for wear and tear of the articular cartilage of joints such as the knee or ankle—essentially early arthritis changes.”

The therapy is predicated on the activity of Interleukin-1 (IL-1). IL-1 is a protein that stimulates the immune system to combat infections, but it can also activate inflammatory cascades that can cause joint degeneration and cartilage destruction. In fact, it is known to play an integral role in joint diseases such as osteoarthritis and intervertebral disc degeneration.

The body also contains a protein called Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA), which inhibits the effects of IL-1. IL-1RA is produced by white blood cells and prevents IL-1 from binding to its receptor, thus reducing the inflammatory effects of IL-1. As part of the Orthokine treatment, IL-1RA is added to the plasma solution that is eventually infused into Kobe’s knee.

The treatment is actually different from platelet-rich plasma (PRP) therapy, a more common procedure. In PRP, the physician obtains a sample of patient blood before spinning it in a centrifuge. This centrifugation separates out a layer containing platelet-rich plasma and various activating factors, both of which are then injected together in their unadulterated form into the area of injury. It is believed that PRP accelerates the healing process.

A long list of athletes have received Orthokine, PRP or a similar treatment. Aside from Bryant, Peyton Manning, Tracy McGrady, Alex Rodriguez, and Tiger Woods are among hundreds of professional athletes who have undergone the procedure.

Neither PRP nor Orthokine are banned by the United States Anti-Doping Agency or the World Anti-Doping Agency. Moreover, Orthokine is not illegal, nor does it involve steroids, human growth hormone or other performance-enhancing substances.

Kobe believes the treatment works for him, but has it been proven effective in medical studies?

“The studies have not been terribly encouraging,” Geier noted. “Some patients tend to get some relief, whereas others do not seem to get much at all. We still think that there is a lot of hope, but there is a lot of work to do to figure out the right formulation.”

A study funded by Wehling found that Orthokine was effective in 67 percent of patients, comparing favorably to those receiving hyaluronic acid (32 percent) or placebo (33 percent). Other studies, though, either paint an incomplete picture or have been questioned by physicians.

Overall, anecdotal results are positive, but medical evidence is lacking. At worst, evidence has yet to suggest the treatment is associated with any immediate or long-term complications.

“There is not much of a downside other than the cost and the fact that it might not work,” Geier believes. “It is certainly better for a lot of things than are cortisone injections, but it is not by any means proven to be a foolproof, cure-all type of procedure.”

Ultimately, if Kobe wants it, then Kobe gets it. The future of the franchise rests on the health of their $48.5 million man, and so the Lakers will support anything that he believes will help.

Kent Smith/Getty Images

Kent Smith/Getty Images

What to Expect from Kobe

Two injuries and 18 months later, no one really knows what to expect from Bryant when he steps onto the court at Staples Center on October 28.

Simply put, his body is not the same after a rash of injuries. He will have to adjust his game. In fact, Kobe may very well become a shell of his former self, a frightening prospect to imagine.

Bryant was clearly a very different player during his short-lived stint in December. Beyond the evident drop in numbers, he avoided going airborne—even when he did, he mainly launched off and landed on his healthy right foot. His agility and speed were impaired as well.

New head coach Byron Scott recognizes the mileage on Kobe’s legs and plans to limit his practice time and in-game minutes. He has asserted that he has a set number in mind, while also conceding that Kobe may even sit out the second night of back-to-back games.

"We have a set amount of minutes. I’m going to stick to my guns if I think that’s going to be in his best interest. One thing I’ll never do is sacrifice a player's health for a basketball game. I won’t do it. If it can hurt him in the long run, I won’t do it. I might get grief and get criticized for it. But in my heart, if I know this is the best for a player, that’s what I’m going to do."

Geier believes that restricting Kobe’s minutes will help not only in keeping the superstar healthy, but also in enabling him to continue playing at a high level.

“You’re trying to make it through an 82-game season and the playoffs, and for a guy later on in his career, limiting minutes can be good—injury or no injury. When you look at Tim Duncan and some other guys that have really played well, their coaches cut way back on their minutes. Manu Ginobili has had a lot of injuries, and they cut his minutes back, and he did a lot better. Because of his chronic knee issues, I think limiting minutes would be beneficial for Kobe.”

Despite months of rehabilitation, hours spent in the training room and flights to Germany for therapy, his return later this month is arguably the first time in his career that the odds are truly against him. Running around on legs that have carried him for more than 54,000 NBA minutes and on a repaired Achilles tendon at age 36, Bryant is an underdog, really.

To argue in favor of Bryant resembling the All-NBA force we all know so well, you cannot rely on medical science or NBA precedent. Instead, you simply have to throw your hands up and say, “Kobe will do it because he is, well, Kobe freaking Bryant.”

Actually, it is not as absurd an argument as it may appear.

For one, Bryant is an exceptional athlete, even now as the elder statesman. That said, as well as he uses his seemingly ageless athleticism, he remains even more remarkable at understanding schemes and pinpointing opponents’ weaknesses. Moreover, his assist-laden 2012-2013 season demonstrates his ability to act as a de facto point guard when needed.

The argument, then, is that Kobe’s athleticism, IQ and drive are far too removed from those of a typical NBA player to assume he will become the latest to fall victim to a torn Achilles tendon. The case is that he has simply worked too hard to return a mere shell of his Black Mamba self.

Geier believes that an appeal to the legend of Kobe Bryant is not a wholly unconvincing argument.

“There is a psychological aspect to recovery. A risk factor for athletes not returning or returning to the same level of play is a fear of re-injury or a fear that they are not going to be as good as they were. The flip side of it is that there seems to be a subset of people that just don’t fall subject to that. They just have a will to exceed and push through it, which is a great. You love to rehab athletes like that. Even as outside observers, most of us see that in Kobe.”

Regardless of the Kobe Bryant that takes the court on October 28, the raucous fans at Staples Center will drown him in waves of cheers, celebrate his every move and forgive his every misstep. Although the lasting images of Kobe’s legacy will represent an incredibly thrilling highlight reel, perhaps the greatest highlights will be seeing him relentlessly grind away through his recent injuries and adjust his game in the waning years of a storybook career.

It is hard to say how the upcoming year will play out for Bryant and the Lakers. Despite his unyielding efforts to recover, the final score will be the same regardless of when it happens:

Father Time 1, Kobe Bryant 0.

As cruel as it is, every athlete, regardless of how great, has to face the undefeated foe that is Father Time.

For the last 18 years, Bryant has put on a fantastic party for Lakers fans and basketball fans worldwide. But the final songs are being played, and it will be closing time before we know it.

Dr. Geier is neither involved in the medical or surgical care of Kobe Bryant nor has access to his personal medical records. His analysis represents speculation based on available information and consults with experts and specialists.

Two injuries and 18 months later, no one really knows what to expect from Bryant when he steps onto the court at Staples Center on October 28.

Simply put, his body is not the same after a rash of injuries. He will have to adjust his game. In fact, Kobe may very well become a shell of his former self, a frightening prospect to imagine.

Bryant was clearly a very different player during his short-lived stint in December. Beyond the evident drop in numbers, he avoided going airborne—even when he did, he mainly launched off and landed on his healthy right foot. His agility and speed were impaired as well.

New head coach Byron Scott recognizes the mileage on Kobe’s legs and plans to limit his practice time and in-game minutes. He has asserted that he has a set number in mind, while also conceding that Kobe may even sit out the second night of back-to-back games.

"We have a set amount of minutes. I’m going to stick to my guns if I think that’s going to be in his best interest. One thing I’ll never do is sacrifice a player's health for a basketball game. I won’t do it. If it can hurt him in the long run, I won’t do it. I might get grief and get criticized for it. But in my heart, if I know this is the best for a player, that’s what I’m going to do."

Geier believes that restricting Kobe’s minutes will help not only in keeping the superstar healthy, but also in enabling him to continue playing at a high level.

“You’re trying to make it through an 82-game season and the playoffs, and for a guy later on in his career, limiting minutes can be good—injury or no injury. When you look at Tim Duncan and some other guys that have really played well, their coaches cut way back on their minutes. Manu Ginobili has had a lot of injuries, and they cut his minutes back, and he did a lot better. Because of his chronic knee issues, I think limiting minutes would be beneficial for Kobe.”

Despite months of rehabilitation, hours spent in the training room and flights to Germany for therapy, his return later this month is arguably the first time in his career that the odds are truly against him. Running around on legs that have carried him for more than 54,000 NBA minutes and on a repaired Achilles tendon at age 36, Bryant is an underdog, really.

To argue in favor of Bryant resembling the All-NBA force we all know so well, you cannot rely on medical science or NBA precedent. Instead, you simply have to throw your hands up and say, “Kobe will do it because he is, well, Kobe freaking Bryant.”

Actually, it is not as absurd an argument as it may appear.

For one, Bryant is an exceptional athlete, even now as the elder statesman. That said, as well as he uses his seemingly ageless athleticism, he remains even more remarkable at understanding schemes and pinpointing opponents’ weaknesses. Moreover, his assist-laden 2012-2013 season demonstrates his ability to act as a de facto point guard when needed.

The argument, then, is that Kobe’s athleticism, IQ and drive are far too removed from those of a typical NBA player to assume he will become the latest to fall victim to a torn Achilles tendon. The case is that he has simply worked too hard to return a mere shell of his Black Mamba self.

Geier believes that an appeal to the legend of Kobe Bryant is not a wholly unconvincing argument.

“There is a psychological aspect to recovery. A risk factor for athletes not returning or returning to the same level of play is a fear of re-injury or a fear that they are not going to be as good as they were. The flip side of it is that there seems to be a subset of people that just don’t fall subject to that. They just have a will to exceed and push through it, which is a great. You love to rehab athletes like that. Even as outside observers, most of us see that in Kobe.”

Regardless of the Kobe Bryant that takes the court on October 28, the raucous fans at Staples Center will drown him in waves of cheers, celebrate his every move and forgive his every misstep. Although the lasting images of Kobe’s legacy will represent an incredibly thrilling highlight reel, perhaps the greatest highlights will be seeing him relentlessly grind away through his recent injuries and adjust his game in the waning years of a storybook career.

It is hard to say how the upcoming year will play out for Bryant and the Lakers. Despite his unyielding efforts to recover, the final score will be the same regardless of when it happens:

Father Time 1, Kobe Bryant 0.

As cruel as it is, every athlete, regardless of how great, has to face the undefeated foe that is Father Time.

For the last 18 years, Bryant has put on a fantastic party for Lakers fans and basketball fans worldwide. But the final songs are being played, and it will be closing time before we know it.

Dr. Geier is neither involved in the medical or surgical care of Kobe Bryant nor has access to his personal medical records. His analysis represents speculation based on available information and consults with experts and specialists.