Mr. T Recounts His Experience with Cutaneous T-cell Lymphoma: An Interview with Ellen J. Kim, M.D.

Published by Daniel Lewis on September 25, 2017 at SB Nation. Click to read article at SB Nation.

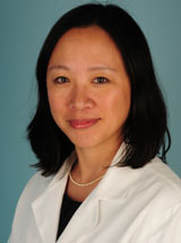

In a one-on-one interview with Ellen J. Kim, M.D., Sandra J. Lazarus Professor of Dermatology at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Dr. Kim and sports journalist Daniel Lewis discuss Mr. T’s longtime battle with mycosis fungoides, a form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

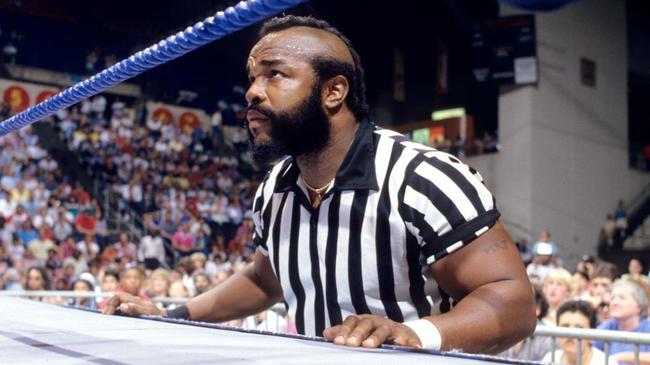

The indomitable Mr. T has served as a WWF wrestler, bodyguard, and star of television’s The A-Team. He even took on Rocky Balboa in the boxing ring in the film Rocky III.

Since then, he has battled a far more dangerous enemy: cancer.

It was in September 1995 when Mr. T, while removing a diamond earring, first noticed a small sore on his ear.

“I’m thinking, ‘Wow, if I’m signing autographs and bending down, people are going to see that little bump’…it was like a little sore,” Mr. T reveals.

When the sore grew over the next two weeks, he decided to visit his primary care doctor. He was later referred to a dermatologist, who was suspicious of the sore and performed a biopsy.

“About a week later…he said, ‘It showed that you have cancer—you’ve got a rare form of cancer.’ So I’m just sitting there, and I said, ‘Wow,’” Mr. T reflects. “It was like a numbness.”

Mr. T was diagnosed with mycosis fungoides (MF), a rare lymphoma that manifests in the skin.

MF is a T-cell lymphoma—a cancer of white blood cells called T lymphocytes, or T cells. Because the cells infiltrate the skin in MF, the disease is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

“Can you imagine that?!” Mr. T exclaims. “Cancer with my name on it—personalized cancer.”

The indomitable Mr. T has served as a WWF wrestler, bodyguard, and star of television’s The A-Team. He even took on Rocky Balboa in the boxing ring in the film Rocky III.

Since then, he has battled a far more dangerous enemy: cancer.

It was in September 1995 when Mr. T, while removing a diamond earring, first noticed a small sore on his ear.

“I’m thinking, ‘Wow, if I’m signing autographs and bending down, people are going to see that little bump’…it was like a little sore,” Mr. T reveals.

When the sore grew over the next two weeks, he decided to visit his primary care doctor. He was later referred to a dermatologist, who was suspicious of the sore and performed a biopsy.

“About a week later…he said, ‘It showed that you have cancer—you’ve got a rare form of cancer.’ So I’m just sitting there, and I said, ‘Wow,’” Mr. T reflects. “It was like a numbness.”

Mr. T was diagnosed with mycosis fungoides (MF), a rare lymphoma that manifests in the skin.

MF is a T-cell lymphoma—a cancer of white blood cells called T lymphocytes, or T cells. Because the cells infiltrate the skin in MF, the disease is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

“Can you imagine that?!” Mr. T exclaims. “Cancer with my name on it—personalized cancer.”

Ellen J. Kim, M.D.

Ellen J. Kim, M.D.

“CTCL represents a collection of several lymphomas primarily affecting the skin,” explains Ellen J. Kim, M.D., Sandra J. Lazarus Professor of Dermatology at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. “The disease is different from most other lymphomas in that it arises from skin T lymphocytes. MF does not start in the bone marrow like a leukemia or in the lymph nodes like most lymphomas.”

“CTCL is a form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and MF is the most common subtype of CTCL. It is rare and makes up only a tiny proportion of all lymphomas—probably 1%.”

Normal T cells are integral in surveying and protecting the human body from infectious agents. As they mature and develop in the bone marrow, they acquire homing signals that direct them to specific body sites. Skin-homing T cells, for example, migrate to the skin after an insult, such as a skin infection. After exterminating the invader, they typically leave the skin, recirculating in the blood or lymphatics to travel to another area within the skin or undergoing natural cell death.

On the other hand, in MF, after the T cells enter the skin, they clone themselves and accumulate instead of recirculating or dying naturally—for reasons that still remain unknown. These collections of T cells in the skin, in turn, become clinically apparent as rashes or red lumps.

Despite its name, which was first used in the 1800s, MF is not a fungal disease.

“The term ‘mycosis fungoides’ is an old, historical name.” Dr. Kim clarifies. “When it was first described, it was thought to be similar to some fungal skin infections. But the name stuck.”

In most patients, MF first appears in the skin as flat, red, scaly lesions known as patches.

“Classically, the patches develop in a ‘bathing trunk distribution’—the lower trunk, hips, or buttocks,” Dr. Kim teaches. “I refer to these areas as places where the sun doesn’t shine.”

As the disease progresses and more T cells accumulate in the skin, the lesions can thicken, producing raised lesions called plaques. Approximately 10-15% of patients progress beyond early-stage disease; in these patients, T cells accumulate in the skin so extensively that disfiguring nodules and tumors develop. These “ball-like” lesions can ulcerate, forming sores.

For his sore, Mr. T received localized radiation delivered to his ear over four weeks.

“It was a month of radiation, and the doctor told me…‘Now, the cancer might come back or it might not. You can’t worry about that. You’ve got to go on and live your life,’” Mr. T recalls.

Eleven months later, unfortunately, Mr. T’s disease returned, and this time, it had worsened.

“Cancer sores sprouting up on my body and I can’t stop it!” Mr. T describes vividly. “I have no control over this cancer…on my arms, my back, my legs, and my stomach….It is cancer popping like microwave popcorn on my body. I am afraid at this point; no tough guy today.”

“Here comes doubt, here comes anxiety, here comes fear, here comes that sick feeling down in the pit of my stomach. Can’t eat, can’t sleep.”

With further progression, the lymphoma cells may lose their skin-homing tendency and invade local lymph nodes and the blood. Sézary syndrome (SS) is an advanced, leukemic form of MF characterized by the presence of a high concentration of malignant cells in the blood. Patients with SS develop extensive itchy red patches affecting over 80 percent of the skin.

The clinical course of MF is highly variable among patients and often unpredictable. However, if progression occurs, it typically takes place over several years or even decades.

Because each patient is different, there is not one “right” treatment for all MF patients.

“Essentially, we decide treatment based on each patient’s age, overall health, and disease stage, which is essentially doctor-speak for ‘where is the cancer?’ Is it just in the skin—and just a little bit or a lot? Is it in the lymph nodes, the blood, or the rest of the body?” asks Dr. Kim.

“I like to divide treatments into three very basic categories: skin-directed, systemic, and clinical trials. Skin-directed agents are basically those that are just applied on or target the skin. They are for more limited disease and generally do not cause internal side effects. Systemic agents are stronger and are given orally, via injections, or intravenously. And then there are clinical trials, which we use to test new therapies so they can get approved by the FDA.”

The goal of skin-directed therapy is to improve the skin lesions. The major agents in this category include topical corticosteroids (triamcinolone, clobetasol), topical retinoids (bexarotene, tazarotene), topical chemotherapy agents (carmustine, mechlorethamine), topical immunotherapy (imiquimod), and localized superficial radiation therapy (electron beam radiation).

Ultraviolet (UV) light, given either as UVA or UVB, is another skin-directed therapy. Whereas UV radiation can lead to other skin cancers, it is actually beneficial in MF and is referred to as “phototherapy” when used as treatment. In fact, the effect of UV light in eradicating the lymphoma cells is one reason why MF mainly affects areas of the body not exposed to sunlight.

Systemic therapies are generally reserved for more advanced disease. Examples include oral retinoids (acitretin, bexarotene)--compounds related to vitamin A that slow cancer cell growth--and histone deacetylase inhibitors (vorinostat, romidepsin), which turn on genes that fight cancer. Mr. T is on another systemic agent known as interferon-alpha, a substance our body also naturally produces on its own to boost its immune defenses against cancers and viruses.

In recent years, many new agents have been developed and investigated for MF. Clinical trials are ongoing to evaluate newer, targeted treatments that may be more safe or effective.

“There is a lot of great research going on,” reveals Dr. Kim. “There are a number of targeted therapies that try to target the advanced-stage cancer cells without affecting normal cells in the body. CTCL is an exciting area right now with a lot of active research.”

Despite these new, revolutionary therapies, unlike most other lymphomas, MF is not curable. Fortunately, most therapies can yield either partial or near-complete remission. Nevertheless, the majority of patients with MF require lifelong treatment and monitoring.

“When you hear the word ‘cancer,’ your mind goes 60 miles an hour. But you also think, ‘I’m ready, just tell me what to do, and I’m going to do it.’ You prioritize it above all else. And that mindset is true for some cancers,” acknowledges Dr. Kim. “For breast cancer, there is an intensive treatment period—you go through surgery, radiation, and maybe chemotherapy—followed by a phase of maintenance hormonal therapy. But you see the finish line, and you can work toward that goal. And that’s something to look forward to.”

“MF is a little different. It is more of a chronic condition. For most patients, this is good news in that it is slow-moving and not immediately life-threatening. But on the flip side, it is very hard to cure. And maybe we don’t need to—maybe we can have people with early-stage disease peacefully coexist with it. ‘Cure’ is a word we tend not to use when talking about MF . We are working very hard towards a cure, but it’s not the situation at the moment unfortunately.”

Despite suffering multiple relapses and cycling through an array of treatments, Mr. T has remained upbeat. He appears to have accepted the reality of his disease.

“Life is an endurance test,” Mr. T explains. “It’s not a fifty-yard sprint or a hundred-yard dash; it’s a marathon….I got to endure, endure the hardship….I’ve been through a lot, you know, there’s been peaks and valleys. Every day you don’t feel 100%, but I made it through.”

“I have grown into a cancer fighter. I am a soldier, a veteran at that. We’re all gonna die eventually from something or other…Put up a good fight. Don’t sit around waiting on death. We can be tough. We can be determined…We can be living with cancer, not always dying from it.”

After experiencing his own battle with cancer, Mr. T has offered his support to other cancer victims. He regularly donates to cancer societies, and he published a book about his struggles, Cancer Saved My Life: Cancer Ain’t for No Wimps, in an effort to motivate others with cancer.

“I say not just to the cancer but to themselves, ‘I pity the fool who don’t fight back,’” Mr. T asserts.

Ellen J. Kim, M.D. is the Sandra J. Lazarus Professor of Dermatology and Co-Director of the Cutaneous Oncology Program at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Dr. Kim is neither involved in the medical care of Mr. T nor has access to his personal medical records. Her analysis represents general information about the care of patients with MF and from Mr. T’s book, Cancer Saved My Life: Cancer Ain’t for No Wimps.

“CTCL is a form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and MF is the most common subtype of CTCL. It is rare and makes up only a tiny proportion of all lymphomas—probably 1%.”

Normal T cells are integral in surveying and protecting the human body from infectious agents. As they mature and develop in the bone marrow, they acquire homing signals that direct them to specific body sites. Skin-homing T cells, for example, migrate to the skin after an insult, such as a skin infection. After exterminating the invader, they typically leave the skin, recirculating in the blood or lymphatics to travel to another area within the skin or undergoing natural cell death.

On the other hand, in MF, after the T cells enter the skin, they clone themselves and accumulate instead of recirculating or dying naturally—for reasons that still remain unknown. These collections of T cells in the skin, in turn, become clinically apparent as rashes or red lumps.

Despite its name, which was first used in the 1800s, MF is not a fungal disease.

“The term ‘mycosis fungoides’ is an old, historical name.” Dr. Kim clarifies. “When it was first described, it was thought to be similar to some fungal skin infections. But the name stuck.”

In most patients, MF first appears in the skin as flat, red, scaly lesions known as patches.

“Classically, the patches develop in a ‘bathing trunk distribution’—the lower trunk, hips, or buttocks,” Dr. Kim teaches. “I refer to these areas as places where the sun doesn’t shine.”

As the disease progresses and more T cells accumulate in the skin, the lesions can thicken, producing raised lesions called plaques. Approximately 10-15% of patients progress beyond early-stage disease; in these patients, T cells accumulate in the skin so extensively that disfiguring nodules and tumors develop. These “ball-like” lesions can ulcerate, forming sores.

For his sore, Mr. T received localized radiation delivered to his ear over four weeks.

“It was a month of radiation, and the doctor told me…‘Now, the cancer might come back or it might not. You can’t worry about that. You’ve got to go on and live your life,’” Mr. T recalls.

Eleven months later, unfortunately, Mr. T’s disease returned, and this time, it had worsened.

“Cancer sores sprouting up on my body and I can’t stop it!” Mr. T describes vividly. “I have no control over this cancer…on my arms, my back, my legs, and my stomach….It is cancer popping like microwave popcorn on my body. I am afraid at this point; no tough guy today.”

“Here comes doubt, here comes anxiety, here comes fear, here comes that sick feeling down in the pit of my stomach. Can’t eat, can’t sleep.”

With further progression, the lymphoma cells may lose their skin-homing tendency and invade local lymph nodes and the blood. Sézary syndrome (SS) is an advanced, leukemic form of MF characterized by the presence of a high concentration of malignant cells in the blood. Patients with SS develop extensive itchy red patches affecting over 80 percent of the skin.

The clinical course of MF is highly variable among patients and often unpredictable. However, if progression occurs, it typically takes place over several years or even decades.

Because each patient is different, there is not one “right” treatment for all MF patients.

“Essentially, we decide treatment based on each patient’s age, overall health, and disease stage, which is essentially doctor-speak for ‘where is the cancer?’ Is it just in the skin—and just a little bit or a lot? Is it in the lymph nodes, the blood, or the rest of the body?” asks Dr. Kim.

“I like to divide treatments into three very basic categories: skin-directed, systemic, and clinical trials. Skin-directed agents are basically those that are just applied on or target the skin. They are for more limited disease and generally do not cause internal side effects. Systemic agents are stronger and are given orally, via injections, or intravenously. And then there are clinical trials, which we use to test new therapies so they can get approved by the FDA.”

The goal of skin-directed therapy is to improve the skin lesions. The major agents in this category include topical corticosteroids (triamcinolone, clobetasol), topical retinoids (bexarotene, tazarotene), topical chemotherapy agents (carmustine, mechlorethamine), topical immunotherapy (imiquimod), and localized superficial radiation therapy (electron beam radiation).

Ultraviolet (UV) light, given either as UVA or UVB, is another skin-directed therapy. Whereas UV radiation can lead to other skin cancers, it is actually beneficial in MF and is referred to as “phototherapy” when used as treatment. In fact, the effect of UV light in eradicating the lymphoma cells is one reason why MF mainly affects areas of the body not exposed to sunlight.

Systemic therapies are generally reserved for more advanced disease. Examples include oral retinoids (acitretin, bexarotene)--compounds related to vitamin A that slow cancer cell growth--and histone deacetylase inhibitors (vorinostat, romidepsin), which turn on genes that fight cancer. Mr. T is on another systemic agent known as interferon-alpha, a substance our body also naturally produces on its own to boost its immune defenses against cancers and viruses.

In recent years, many new agents have been developed and investigated for MF. Clinical trials are ongoing to evaluate newer, targeted treatments that may be more safe or effective.

“There is a lot of great research going on,” reveals Dr. Kim. “There are a number of targeted therapies that try to target the advanced-stage cancer cells without affecting normal cells in the body. CTCL is an exciting area right now with a lot of active research.”

Despite these new, revolutionary therapies, unlike most other lymphomas, MF is not curable. Fortunately, most therapies can yield either partial or near-complete remission. Nevertheless, the majority of patients with MF require lifelong treatment and monitoring.

“When you hear the word ‘cancer,’ your mind goes 60 miles an hour. But you also think, ‘I’m ready, just tell me what to do, and I’m going to do it.’ You prioritize it above all else. And that mindset is true for some cancers,” acknowledges Dr. Kim. “For breast cancer, there is an intensive treatment period—you go through surgery, radiation, and maybe chemotherapy—followed by a phase of maintenance hormonal therapy. But you see the finish line, and you can work toward that goal. And that’s something to look forward to.”

“MF is a little different. It is more of a chronic condition. For most patients, this is good news in that it is slow-moving and not immediately life-threatening. But on the flip side, it is very hard to cure. And maybe we don’t need to—maybe we can have people with early-stage disease peacefully coexist with it. ‘Cure’ is a word we tend not to use when talking about MF . We are working very hard towards a cure, but it’s not the situation at the moment unfortunately.”

Despite suffering multiple relapses and cycling through an array of treatments, Mr. T has remained upbeat. He appears to have accepted the reality of his disease.

“Life is an endurance test,” Mr. T explains. “It’s not a fifty-yard sprint or a hundred-yard dash; it’s a marathon….I got to endure, endure the hardship….I’ve been through a lot, you know, there’s been peaks and valleys. Every day you don’t feel 100%, but I made it through.”

“I have grown into a cancer fighter. I am a soldier, a veteran at that. We’re all gonna die eventually from something or other…Put up a good fight. Don’t sit around waiting on death. We can be tough. We can be determined…We can be living with cancer, not always dying from it.”

After experiencing his own battle with cancer, Mr. T has offered his support to other cancer victims. He regularly donates to cancer societies, and he published a book about his struggles, Cancer Saved My Life: Cancer Ain’t for No Wimps, in an effort to motivate others with cancer.

“I say not just to the cancer but to themselves, ‘I pity the fool who don’t fight back,’” Mr. T asserts.

Ellen J. Kim, M.D. is the Sandra J. Lazarus Professor of Dermatology and Co-Director of the Cutaneous Oncology Program at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Dr. Kim is neither involved in the medical care of Mr. T nor has access to his personal medical records. Her analysis represents general information about the care of patients with MF and from Mr. T’s book, Cancer Saved My Life: Cancer Ain’t for No Wimps.