Terry Bradshaw Talks Herpes Zoster and Vaccine: An Interview with Stephen K. Tyring, M.D., Ph.D., M.B.A.

Published by Daniel Lewis on December 30, 2017 at SB Nation. Click to read article at SB Nation.

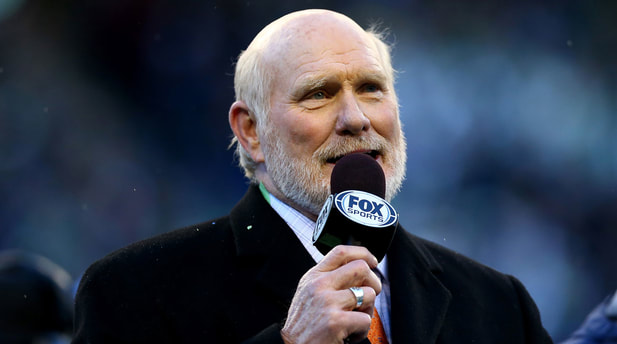

Getty Images

Getty Images

In a one-on-one interview with Stephen K. Tyring, M.D., Ph.D., M.B.A., Medical Director of the Center for Clinical Studies and Clinical Professor in the Departments of Dermatology and Microbiology & Molecular Genetics at the McGovern Medical School, Dr. Tyring and sports journalist Daniel Lewis discuss Terry Bradshaw’s ad campaign for the herpes zoster (shingles) vaccine and discuss the clinical features, complications, and treatments of herpes zoster.

NFL Hall-of-Fame NFL quarterback Terry Bradshaw guided the Pittsburgh Steelers to the football mountaintop after hoisting the Lombardi Trophy four times in the 1970s and 80s.

Years after climbing that mountain, though, Bradshaw still feels the effects of the countless hits he endured during his 13-year career on the gridiron.

“I got knocked out on the opening drive, KO’d, flat out on my feet,” the 69-year-old Bradshaw recalls, describing one playoff game.

Despite the weekly barrage of opposing linemen, Bradshaw believes he experienced something far more painful than being thrown to the ground by oversized defenders.

“If you play football for a long time like I did, you’re going to learn to deal with a lot of pain.”

“But it is nothing like the pain shingles causes.”

“The pain associated with shingles can be very excruciating,” states Stephen K. Tyring, M.D., Ph.D., M.B.A., Medical Director of the Center for Clinical Studies and Clinical Professor in the Departments of Dermatology and Microbiology & Molecular Genetics at the McGovern Medical School.

NFL Hall-of-Fame NFL quarterback Terry Bradshaw guided the Pittsburgh Steelers to the football mountaintop after hoisting the Lombardi Trophy four times in the 1970s and 80s.

Years after climbing that mountain, though, Bradshaw still feels the effects of the countless hits he endured during his 13-year career on the gridiron.

“I got knocked out on the opening drive, KO’d, flat out on my feet,” the 69-year-old Bradshaw recalls, describing one playoff game.

Despite the weekly barrage of opposing linemen, Bradshaw believes he experienced something far more painful than being thrown to the ground by oversized defenders.

“If you play football for a long time like I did, you’re going to learn to deal with a lot of pain.”

“But it is nothing like the pain shingles causes.”

“The pain associated with shingles can be very excruciating,” states Stephen K. Tyring, M.D., Ph.D., M.B.A., Medical Director of the Center for Clinical Studies and Clinical Professor in the Departments of Dermatology and Microbiology & Molecular Genetics at the McGovern Medical School.

Stephen K. Tyring, M.D., Ph.D., M.B.A.

Stephen K. Tyring, M.D., Ph.D., M.B.A.

“Many patients with shingles say that it is more painful than their previous heart attacks, automobile accidents, or bullet wounds during the war,” describes Dr. Tyring. “Many women describe it as more painful than childbirth without anesthesia.”

“Man, when I got shingles, it was something awful,” admits Bradshaw. “It was like being blindsided by some linebacker…couldn’t see it coming…It can hit you out of nowhere…Boom! Take it from a guy who has had his fair share of pain.”

Shingles is caused by the varicella-zoster virus, which, as its name indicates, causes two distinct infections. The first one is varicella, or more commonly known as chickenpox. Chickenpox often presents in children, causing blisters that first appear on the back, chest, and face before they spread to the rest of the body. After chickenpox runs its itchy course, the virus retreats to nerve bodies near the brain and spinal cord, where it can lay dormant for years.

For reasons that remain unknown, the virus later “wakes up” and travels along nerve fibers projecting to the skin, which leads to its second infection: shingles. Therefore, anyone who suffers from shingles must have first experienced chickenpox, typically during childhood.

“If you have had chickenpox, then that shingles virus is already inside you,” explains Bradshaw. “And it ain’t pretty when it comes out.”

Bradshaw has been very vocal about his bout of shingles and often appears in television commercials sponsored by Merck & Co. in which he urges viewers to get the vaccine.

“One out of three people are going to end up getting shingles,” he declares. “I was one of them.”

During these commercials, Bradshaw often shows pictures of the types of lesions he developed.

“When I got shingles…it was this painful rash…I had this ugly band of blisters. Little blisters, red ugly stuff—lots of them. That nasty rash can pop up anywhere, and the pain can be even worse than it looks.”

There are specific clinical features, teaches Dr. Tyring, that are classic for shingles.

“The first hint is pain on one side of the body. The pain almost always precedes any redness, bumps, or blisters. The blisters are usually the first diagnostic sign for us physicians, but they do not appear until 2 or 3 days after the pain begins.”

“Blisters following the distribution of a nerve, associated with pain, is shingles unless proven otherwise,” clarifies Dr. Tyring. “Shingles is unique in that it causes blisters and pain on one side of the body. They can be on one side of the face, trunk, or abdomen, or they can go down one arm or leg. Except in rare cases in certain patients, they do not cross to the other side.”

Even after the lesions resolve, up to 15% of individuals may suffer from deep nerve pain termed post-herpetic neuralgia. This pain can persist for months or even years, especially in older people.

“The usual worst case scenario with shingles is damage to the nerve, which causes long-term, residual pain known as post-herpetic neuralgia. It is essentially pain after healing of the skin.”

“The reason why shingles is so painful is that it is basically a nerve infection. And so when we treat shingles, we usually give oral antivirals such as acyclovir or valcyclovir instead of recommending a cream for the skin—because we are trying to target the infected nerve.”

However, shingles can cause complications other than post-herpetic neuralgia, as Dr. Tyring explains. For example, if it affects the eye, it can cause a syndrome known as herpes zoster ophthalmicus; if it involves the ear, it can lead to Ramsey-Hunt syndrome.

“If shingles affects the nerve innervating the eye, it can cause loss of vision or even total blindness. If it affects the nerve that goes to the ear, it can cause loss of balance. These rare manifestations of shingles can be very serious, and so they should be treated immediately.”

Indeed, the main objectives in treating shingles involve (1) controlling the acute pain, (2) clearing the rash quickly, and (3) reducing the risk of complications.

“The most important aspect of shingles is to treat it early if it occurs to prevent it from damaging the nerve further—or to prevent it altogether with the vaccine.”

The vaccine, known as Zostavax®, is a live-attenuated vaccine, meaning it is composed of a weakened version of the virus. The vaccine has been available since 2006.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends Zostavax® in individuals age 50 and older, in accordance with the age at which the incidence of shingles sharply increases. It is recommended even in individuals who do not remember having experienced chickenpox as a child because there is a high likelihood that they did.

Bradshaw openly endorses the vaccine during his commercial appearances, and Dr. Tyring notes that it is more effective than the data might initially appear to show.

“In early studies, the efficacy of the vaccine in people over 60 was 51%, which sounds pretty low—except the 49% who developed shingles despite the vaccine had a 2/3rds reduction in the intensity and duration of the pain, so it actually did benefit them too.”

“And those who got the vaccine in their 50s in later studies did even better…They had a 70% reduction in shingles, and the remaining 30% had a significant reduction in the intensity and duration of the pain.”

Even more reinforcements against shingles are on the way. A new vaccine, GlaxoSmithKline’s Shingrix®, was recently approved by the FDA. Classified as a subunit vaccine, the new vaccine differs from Zostavax® in that it does not contain the entire viral molecule—it only contains the specific viral proteins that stimulate our immunity to the virus.

As such, Shingrix® is not only more effective than the old vaccine, but its protection also lasts longer, and it can also be given to immunocompromised patients. In fact, the Center for Disease Control now recommends Shingrix® over Zostavax® because of these advantages.

“There has been a lot of progress in recent years. It is an exciting time for research on shingles.”

Dr. Tyring is neither involved in the medical care of Terry Bradshaw nor has access to his personal medical records. His analysis represents his clinical and research expertise on the varicella-zoster virus and the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of herpes zoster.

“Man, when I got shingles, it was something awful,” admits Bradshaw. “It was like being blindsided by some linebacker…couldn’t see it coming…It can hit you out of nowhere…Boom! Take it from a guy who has had his fair share of pain.”

Shingles is caused by the varicella-zoster virus, which, as its name indicates, causes two distinct infections. The first one is varicella, or more commonly known as chickenpox. Chickenpox often presents in children, causing blisters that first appear on the back, chest, and face before they spread to the rest of the body. After chickenpox runs its itchy course, the virus retreats to nerve bodies near the brain and spinal cord, where it can lay dormant for years.

For reasons that remain unknown, the virus later “wakes up” and travels along nerve fibers projecting to the skin, which leads to its second infection: shingles. Therefore, anyone who suffers from shingles must have first experienced chickenpox, typically during childhood.

“If you have had chickenpox, then that shingles virus is already inside you,” explains Bradshaw. “And it ain’t pretty when it comes out.”

Bradshaw has been very vocal about his bout of shingles and often appears in television commercials sponsored by Merck & Co. in which he urges viewers to get the vaccine.

“One out of three people are going to end up getting shingles,” he declares. “I was one of them.”

During these commercials, Bradshaw often shows pictures of the types of lesions he developed.

“When I got shingles…it was this painful rash…I had this ugly band of blisters. Little blisters, red ugly stuff—lots of them. That nasty rash can pop up anywhere, and the pain can be even worse than it looks.”

There are specific clinical features, teaches Dr. Tyring, that are classic for shingles.

“The first hint is pain on one side of the body. The pain almost always precedes any redness, bumps, or blisters. The blisters are usually the first diagnostic sign for us physicians, but they do not appear until 2 or 3 days after the pain begins.”

“Blisters following the distribution of a nerve, associated with pain, is shingles unless proven otherwise,” clarifies Dr. Tyring. “Shingles is unique in that it causes blisters and pain on one side of the body. They can be on one side of the face, trunk, or abdomen, or they can go down one arm or leg. Except in rare cases in certain patients, they do not cross to the other side.”

Even after the lesions resolve, up to 15% of individuals may suffer from deep nerve pain termed post-herpetic neuralgia. This pain can persist for months or even years, especially in older people.

“The usual worst case scenario with shingles is damage to the nerve, which causes long-term, residual pain known as post-herpetic neuralgia. It is essentially pain after healing of the skin.”

“The reason why shingles is so painful is that it is basically a nerve infection. And so when we treat shingles, we usually give oral antivirals such as acyclovir or valcyclovir instead of recommending a cream for the skin—because we are trying to target the infected nerve.”

However, shingles can cause complications other than post-herpetic neuralgia, as Dr. Tyring explains. For example, if it affects the eye, it can cause a syndrome known as herpes zoster ophthalmicus; if it involves the ear, it can lead to Ramsey-Hunt syndrome.

“If shingles affects the nerve innervating the eye, it can cause loss of vision or even total blindness. If it affects the nerve that goes to the ear, it can cause loss of balance. These rare manifestations of shingles can be very serious, and so they should be treated immediately.”

Indeed, the main objectives in treating shingles involve (1) controlling the acute pain, (2) clearing the rash quickly, and (3) reducing the risk of complications.

“The most important aspect of shingles is to treat it early if it occurs to prevent it from damaging the nerve further—or to prevent it altogether with the vaccine.”

The vaccine, known as Zostavax®, is a live-attenuated vaccine, meaning it is composed of a weakened version of the virus. The vaccine has been available since 2006.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends Zostavax® in individuals age 50 and older, in accordance with the age at which the incidence of shingles sharply increases. It is recommended even in individuals who do not remember having experienced chickenpox as a child because there is a high likelihood that they did.

Bradshaw openly endorses the vaccine during his commercial appearances, and Dr. Tyring notes that it is more effective than the data might initially appear to show.

“In early studies, the efficacy of the vaccine in people over 60 was 51%, which sounds pretty low—except the 49% who developed shingles despite the vaccine had a 2/3rds reduction in the intensity and duration of the pain, so it actually did benefit them too.”

“And those who got the vaccine in their 50s in later studies did even better…They had a 70% reduction in shingles, and the remaining 30% had a significant reduction in the intensity and duration of the pain.”

Even more reinforcements against shingles are on the way. A new vaccine, GlaxoSmithKline’s Shingrix®, was recently approved by the FDA. Classified as a subunit vaccine, the new vaccine differs from Zostavax® in that it does not contain the entire viral molecule—it only contains the specific viral proteins that stimulate our immunity to the virus.

As such, Shingrix® is not only more effective than the old vaccine, but its protection also lasts longer, and it can also be given to immunocompromised patients. In fact, the Center for Disease Control now recommends Shingrix® over Zostavax® because of these advantages.

“There has been a lot of progress in recent years. It is an exciting time for research on shingles.”

Dr. Tyring is neither involved in the medical care of Terry Bradshaw nor has access to his personal medical records. His analysis represents his clinical and research expertise on the varicella-zoster virus and the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of herpes zoster.