No-Huddle Offenses Are Taking Over the NFL—And They Are Here to Stay

Published by Daniel Lewis (Featured Contributor) on September 23, 2012 at Yahoo! Sports. Click to download article.

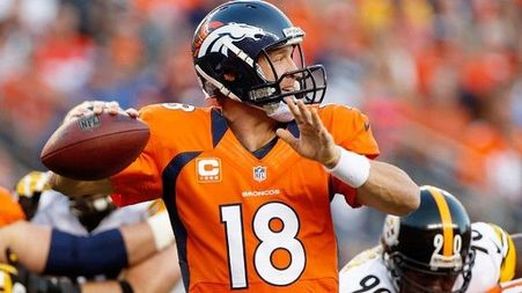

Doug Pensinger/Getty Images

Doug Pensinger/Getty Images

The offensive huddle is quickly becoming an archaism in the NFL.

Though the huddle is far from endangered, the first three weeks of the 2012 NFL season have shown that the league is inching toward a future in which teams will predominantly run no-huddle or hurry-up offenses.

According to Kevin Clark of The Wall Street Journal, 14 percent of offensive plays were set up without a huddle in week one. This number represents an increase of 56 percent from last year and 100 percent from five seasons ago.

In fact, the new season has spawned a new generation of no-huddle quarterbacks in the NFL. Peyton Manning and Tom Brady are longtime emperors of the no-huddle offense, but Matt Ryan and Joe Flacco have joined the ranks of no-huddle signalcallers this season, with several other passers using it on a part-time basis.

This trend is a logical progression in the evolution of the game. It is the latest response from the offense in the back-and-forth struggle between offenses and defenses that has been going on since the game’s inception.

Modern defenses want to match offenses in terms of strength and speed via personnel substitutions, while also attempting to confuse offenses with player movement and disguised coverages and blitzes. However, coaches have begun to use an up-tempo style of play to stymie this sort of defensive tactics.

By taking the huddle out of the equation and heading right to the line of scrimmage, the offense asserts its inherent advantage and leaves the defense with less time to adjust. It also prevents coaches from making substitutions and forces players to improvise instead of having 40 seconds to get input from the sideline or think about assignments for the upcoming play.

Moreover, the no-huddle forces the defense to show its hand, preventing them from disguising schemes or moving around because the quarterback can snap the ball at any time and catch defenses red-handed and off-guard.

As a result, the quarterback running a no-huddle offense sees defenses that are simple. In fact, many defenses often default to "Cover 2" or "Prevent" defenses when an offense goes no-huddle, and these schemes are vulnerable to basic passing plays.

Therein lays the biggest advantage of the no-huddle offense: The defense is forced to play a "vanilla" scheme, and the cerebral quarterback can simply swap into a better play after recognizing a particular scheme.

Manning used this simple formula in running a well-oiled, no-huddle Indianapolis Colts offense for over a decade.

There are only so many ways to disguise a defense. Giving quarterbacks such as Manning more time to read the defense only increases their chances of finding spots where the defense is vulnerable.

The Colts’ offense was, structurally at least, arguably the simplest in the league for the entire time Manning was there. In essence, they used only a handful of formations and ran a small group of core running and passing plays.

Manning and the Colts were able to orchestrate such a simple offense with great success because the no-huddle often handcuffed the defense into playing such simple coverages.

The former Colts quarterback could, because the formations were simple, identify weak spots in the defense and check into the right plays. This reasoning explains why Manning, in the past as a Colt and now as a Bronco, is often seen audibling and gyrating behind center to get the exact play that would exploit the defense right in front of him.

In fact, Manning is headed to the Hall of Fame on the first ballot in no small part because he can count. Over the years, Manning has made a living simply counting the number of defenders in the box. If there are six people in the box, he calls a running play, whereas if there are seven or eight, he throws the ball. In short, he probes the defense and exploits the right matchups.

In this way, the no-huddle offense can help the running game as well. If the offense catches the defense in a nickel or dime package or in an uneven front, a simple handoff can result in a huge gain.

Most of the teams running a lot of no-huddle have superb quarterbacks. While this correlation may be by necessity in that quarterbacks are being tasked with reacting to what they see rather than on what coaches might anticipate, the no-huddle brings out the best in these quarterbacks and is a key reason for their success. In fact, the ones who can execute it best can be, when they settle into a rhythm and have the right weapons, nearly impossible to slow down.

With more possessions come more cracks at the end zone. In 2004, Manning set a then-record of 49 touchdowns. Games became sprints, and huddling became nothing more a way to waste time in the later portions of a game.

By 2007, Brady had grown accustomed to the no-huddle, and his offense set the record for most points in a season (589), most touchdowns by a quarterback (50), and most touchdowns by a receiver (23, by Randy Moss).

These record-breaking offenses were successful in large part because of the no-huddle.

On the other hand, summoning a huddle after each offensive play slows the offense to a halt, which poses a problem not only in-game, but also in practice in that it causes the offense to get fewer reps.

Most importantly, though, a huddle leads coaches to transform plays that can be communicated in just one or two words into long-winded monstrosities. Indeed, the hand signals of the no-huddle can easily convey the very same information.

Expect more quarterbacks to adopt the no-huddle until defenses figure out a way to stop it. Indeed, the no-huddle offense is far from a fad, and it figures to be around for a while.

Though the huddle is far from endangered, the first three weeks of the 2012 NFL season have shown that the league is inching toward a future in which teams will predominantly run no-huddle or hurry-up offenses.

According to Kevin Clark of The Wall Street Journal, 14 percent of offensive plays were set up without a huddle in week one. This number represents an increase of 56 percent from last year and 100 percent from five seasons ago.

In fact, the new season has spawned a new generation of no-huddle quarterbacks in the NFL. Peyton Manning and Tom Brady are longtime emperors of the no-huddle offense, but Matt Ryan and Joe Flacco have joined the ranks of no-huddle signalcallers this season, with several other passers using it on a part-time basis.

This trend is a logical progression in the evolution of the game. It is the latest response from the offense in the back-and-forth struggle between offenses and defenses that has been going on since the game’s inception.

Modern defenses want to match offenses in terms of strength and speed via personnel substitutions, while also attempting to confuse offenses with player movement and disguised coverages and blitzes. However, coaches have begun to use an up-tempo style of play to stymie this sort of defensive tactics.

By taking the huddle out of the equation and heading right to the line of scrimmage, the offense asserts its inherent advantage and leaves the defense with less time to adjust. It also prevents coaches from making substitutions and forces players to improvise instead of having 40 seconds to get input from the sideline or think about assignments for the upcoming play.

Moreover, the no-huddle forces the defense to show its hand, preventing them from disguising schemes or moving around because the quarterback can snap the ball at any time and catch defenses red-handed and off-guard.

As a result, the quarterback running a no-huddle offense sees defenses that are simple. In fact, many defenses often default to "Cover 2" or "Prevent" defenses when an offense goes no-huddle, and these schemes are vulnerable to basic passing plays.

Therein lays the biggest advantage of the no-huddle offense: The defense is forced to play a "vanilla" scheme, and the cerebral quarterback can simply swap into a better play after recognizing a particular scheme.

Manning used this simple formula in running a well-oiled, no-huddle Indianapolis Colts offense for over a decade.

There are only so many ways to disguise a defense. Giving quarterbacks such as Manning more time to read the defense only increases their chances of finding spots where the defense is vulnerable.

The Colts’ offense was, structurally at least, arguably the simplest in the league for the entire time Manning was there. In essence, they used only a handful of formations and ran a small group of core running and passing plays.

Manning and the Colts were able to orchestrate such a simple offense with great success because the no-huddle often handcuffed the defense into playing such simple coverages.

The former Colts quarterback could, because the formations were simple, identify weak spots in the defense and check into the right plays. This reasoning explains why Manning, in the past as a Colt and now as a Bronco, is often seen audibling and gyrating behind center to get the exact play that would exploit the defense right in front of him.

In fact, Manning is headed to the Hall of Fame on the first ballot in no small part because he can count. Over the years, Manning has made a living simply counting the number of defenders in the box. If there are six people in the box, he calls a running play, whereas if there are seven or eight, he throws the ball. In short, he probes the defense and exploits the right matchups.

In this way, the no-huddle offense can help the running game as well. If the offense catches the defense in a nickel or dime package or in an uneven front, a simple handoff can result in a huge gain.

Most of the teams running a lot of no-huddle have superb quarterbacks. While this correlation may be by necessity in that quarterbacks are being tasked with reacting to what they see rather than on what coaches might anticipate, the no-huddle brings out the best in these quarterbacks and is a key reason for their success. In fact, the ones who can execute it best can be, when they settle into a rhythm and have the right weapons, nearly impossible to slow down.

With more possessions come more cracks at the end zone. In 2004, Manning set a then-record of 49 touchdowns. Games became sprints, and huddling became nothing more a way to waste time in the later portions of a game.

By 2007, Brady had grown accustomed to the no-huddle, and his offense set the record for most points in a season (589), most touchdowns by a quarterback (50), and most touchdowns by a receiver (23, by Randy Moss).

These record-breaking offenses were successful in large part because of the no-huddle.

On the other hand, summoning a huddle after each offensive play slows the offense to a halt, which poses a problem not only in-game, but also in practice in that it causes the offense to get fewer reps.

Most importantly, though, a huddle leads coaches to transform plays that can be communicated in just one or two words into long-winded monstrosities. Indeed, the hand signals of the no-huddle can easily convey the very same information.

Expect more quarterbacks to adopt the no-huddle until defenses figure out a way to stop it. Indeed, the no-huddle offense is far from a fad, and it figures to be around for a while.