Pay for Play: College Athletes Deserve to Be Paid

Published by Nicholas Greiner (Columnist), Edited by Daniel Lewis (Editor-in-Chief) on November 16, 2012 in The Penn Sport Report. Click to read article in The Penn Sport Report.

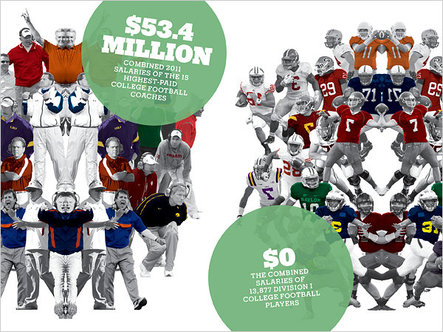

Sara Cwynar/The New York Times

Sara Cwynar/The New York Times

One of the oldest debates surrounding college sports is whether or not the athletes should be paid. Those in favor of payment cite the sums of money brought in by star players in professional sports such as football, basketball, and baseball. Those against the idea say that the scholarship is a form of payment already.

That is where settling of this debate needs to begin. How much does an athlete really make for the school, and what is the value of the scholarship?

According to The New York Times, some experts calculate that the average value of a scholarship awarded to a college athlete falls about $3,500 short per year of meeting the cost of college life. It was not until two years ago that colleges had the option of offering four-year scholarships.

In addition, a student could have his or her funding cut because of an injury or a number of other reasons that could possibly warrant the loss of a scholarship. This situation forces athletes every year to withdraw from school or figure out another way to pay for their education.

Plans made by the NCAA to offer a $2,000 stipend in order to cover the costs of college were rejected by the universities that claimed it would cause budgetary problems. The stipend may be implemented in the future, but for now, it is off the table.

The rules on student athletes are incredibly stringent. An athlete who accepts a free meal from a family friend or fan can face the wrath of the NCAA. Yet with the big business of college sports growing each year as schools find more ways to make big profits off their “student athletes,” the athletes fall farther and farther behind.

Another downside of the current rules is that they force talented high school students to enter college when they could make money straight out of high school. Talented artists can sell paintings for a living and never go to college, but talented basketball players must attend college for one year before they can profit on their talents.

Of course, there is one alternative that is becoming more popular with top players. Basketball players can choose to play a season overseas until they become eligible for the NBA draft.

If a top high school football recruit suffers a career-ending injury during his sophomore year of college, he will never see a dime for the work he has put in on and off the field during both his two years of college and during his high school career.

Had he instead invested that time at even a minimum wage job, he would at least have some financial benefit. Assume that this athlete had put forth four hours of effort, six days a week, for the past five years in order to make it to his level. Working at a minimum wage job, he would have accumulated over $45,000 had he spent those hours working instead of practicing football.

Now most people will correctly point out that some sports are less popular than others in college and that those athletes would probably earn less if the market controlled scholarships and endorsements.

So how would a system paying athletes actually work? Would each sport make the same amount of money or would each sport get to award money based on the amount of revenue generated? Should certain athletes make more than other teammates?

Most people would agree that athletes deserve to have a certain standard of living in college. Too often we see college athletes who are nationally renowned living in poverty or close to it, such as the Fab Five.

The rules do not allow for any additional financial support to athletes who come from disadvantaged backgrounds, often causing less fortunate players to live in harsh conditions.

Companies such as Nike and Reebok exist to turn a profit. The goal of universities should be to educate the youth and foster growth in their communities. That said, athletes should be allowed to sign endorsement deals while in college while still being prohibited from receiving university money beyond what their scholarships already allow.

Under this system, the star college quarterback will still make more than the backup kicker, as the case would be if he were to go on to play in the NFL. Athletes in sports generating more money will still be paid more than athletes who play sports that are less popular.

It is hard to argue that every athlete, regardless of sport or status, should be paid the same amount. In the job market, this situation would never happen. A company’s CEO is paid more than the truck driver because the CEO adds more value to the company.

Athletes in niche markets such as Baylor women’s basketball, Duke lacrosse, Northwestern women’s lacrosse, or Boston College hockey would still have an opportunity to make money.

However, to assume that all sports are created equal is a fallacy in most cases.

Revisiting the Fab Five, if Chris Webber and Jalen Rose had been able to sign shoe deals while still playing at Michigan, then they would have had warm clothes for the winter and would not have had to worry about when they would see their next meal.

At the same time, scholarships should represent a four-year commitment to which the universities are bound. If a star player gets injured, his or her endorsement deals may vanish, but at least he or she will have the opportunity to finish college.

This rule might cause athletic departments to cut some sports; however the trade-off is a favorable one. It seems fairer to guarantee most college athletes a four-year education than to make all players hope they stay healthy and able to produce on the field of play.

With billions of dollars entangled in March Madness and BCS bowl games, surely there are a few thousand dollars in it for the athletes. Covering the costs of living seems to be the smallest way for companies such as Nike and Adidas to reward the athletes.

After all, their numbers and jerseys are profitable, and these companies make money off all the top players. Everyone else in the college sports industry is getting paid, and the players that make that market possible deserve to be paid too.

That is where settling of this debate needs to begin. How much does an athlete really make for the school, and what is the value of the scholarship?

According to The New York Times, some experts calculate that the average value of a scholarship awarded to a college athlete falls about $3,500 short per year of meeting the cost of college life. It was not until two years ago that colleges had the option of offering four-year scholarships.

In addition, a student could have his or her funding cut because of an injury or a number of other reasons that could possibly warrant the loss of a scholarship. This situation forces athletes every year to withdraw from school or figure out another way to pay for their education.

Plans made by the NCAA to offer a $2,000 stipend in order to cover the costs of college were rejected by the universities that claimed it would cause budgetary problems. The stipend may be implemented in the future, but for now, it is off the table.

The rules on student athletes are incredibly stringent. An athlete who accepts a free meal from a family friend or fan can face the wrath of the NCAA. Yet with the big business of college sports growing each year as schools find more ways to make big profits off their “student athletes,” the athletes fall farther and farther behind.

Another downside of the current rules is that they force talented high school students to enter college when they could make money straight out of high school. Talented artists can sell paintings for a living and never go to college, but talented basketball players must attend college for one year before they can profit on their talents.

Of course, there is one alternative that is becoming more popular with top players. Basketball players can choose to play a season overseas until they become eligible for the NBA draft.

If a top high school football recruit suffers a career-ending injury during his sophomore year of college, he will never see a dime for the work he has put in on and off the field during both his two years of college and during his high school career.

Had he instead invested that time at even a minimum wage job, he would at least have some financial benefit. Assume that this athlete had put forth four hours of effort, six days a week, for the past five years in order to make it to his level. Working at a minimum wage job, he would have accumulated over $45,000 had he spent those hours working instead of practicing football.

Now most people will correctly point out that some sports are less popular than others in college and that those athletes would probably earn less if the market controlled scholarships and endorsements.

So how would a system paying athletes actually work? Would each sport make the same amount of money or would each sport get to award money based on the amount of revenue generated? Should certain athletes make more than other teammates?

Most people would agree that athletes deserve to have a certain standard of living in college. Too often we see college athletes who are nationally renowned living in poverty or close to it, such as the Fab Five.

The rules do not allow for any additional financial support to athletes who come from disadvantaged backgrounds, often causing less fortunate players to live in harsh conditions.

Companies such as Nike and Reebok exist to turn a profit. The goal of universities should be to educate the youth and foster growth in their communities. That said, athletes should be allowed to sign endorsement deals while in college while still being prohibited from receiving university money beyond what their scholarships already allow.

Under this system, the star college quarterback will still make more than the backup kicker, as the case would be if he were to go on to play in the NFL. Athletes in sports generating more money will still be paid more than athletes who play sports that are less popular.

It is hard to argue that every athlete, regardless of sport or status, should be paid the same amount. In the job market, this situation would never happen. A company’s CEO is paid more than the truck driver because the CEO adds more value to the company.

Athletes in niche markets such as Baylor women’s basketball, Duke lacrosse, Northwestern women’s lacrosse, or Boston College hockey would still have an opportunity to make money.

However, to assume that all sports are created equal is a fallacy in most cases.

Revisiting the Fab Five, if Chris Webber and Jalen Rose had been able to sign shoe deals while still playing at Michigan, then they would have had warm clothes for the winter and would not have had to worry about when they would see their next meal.

At the same time, scholarships should represent a four-year commitment to which the universities are bound. If a star player gets injured, his or her endorsement deals may vanish, but at least he or she will have the opportunity to finish college.

This rule might cause athletic departments to cut some sports; however the trade-off is a favorable one. It seems fairer to guarantee most college athletes a four-year education than to make all players hope they stay healthy and able to produce on the field of play.

With billions of dollars entangled in March Madness and BCS bowl games, surely there are a few thousand dollars in it for the athletes. Covering the costs of living seems to be the smallest way for companies such as Nike and Adidas to reward the athletes.

After all, their numbers and jerseys are profitable, and these companies make money off all the top players. Everyone else in the college sports industry is getting paid, and the players that make that market possible deserve to be paid too.