The Most Dangerous Game: Former Pro-Bowl QB Mike Boryla Talks NFL Concussions

Published by Daniel Lewis (Featured Contributor) on January 5, 2014 at Yahoo! Sports. Click to download article from Yahoo!

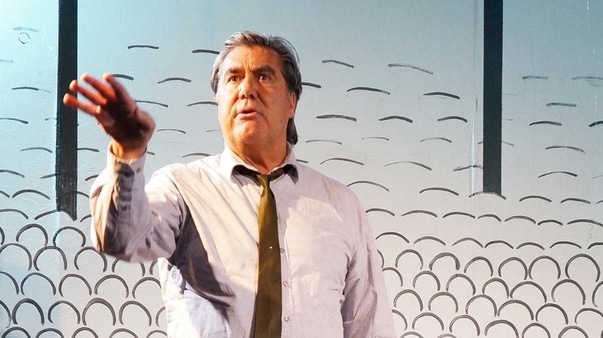

Trevor Reynolds/NewsWorks

Trevor Reynolds/NewsWorks

In a one-on-one interview with Mike Boryla, current playwright and former Pro-Bowl quarterback for the Philadelphia Eagles, Boryla and sports journalist Daniel Lewis discuss concussions in the NFL, Boryla's personal experience with concussions, and legislative attempts to protect individuals from the dangers of football.

As I walk into Philadelphia’s Plays & Players Theatre on a snowy January afternoon, I watch Mike Boryla on stage as he portrays his experience of a concussion during a rehearsal for his one-man play, The Disappearing Quarterback.

“Wow, who are these people?” he asks, with a look of befuddlement plastered on his face. “Why are they looking at me? They all look so nervous and worried. Why are you shining that light in my eyes? It’s so bright. And what kind of building is this? There’s no roof on it. Why not?”

“Name? What’s a name? What are you talking about?”

“Why am I crying so hard? What am I doing here? Where am I? Who am I?”

In his play premiering on January 23, Boryla has a story to tell—a story about what professional football does to its players, and what happens to them after they retire.

A standout player at Stanford, Boryla replaced Roman Gabriel as the Eagles quarterback in 1975 before giving way to Ron Jaworski and ultimately to a series of concussions. He retired at the height of his career, making the decision to walk away primarily because of his fears about concussions.

In fact, during his five years in the league, Boryla grew progressively irked by the NFL culture that treated concussions as harmless injuries.

“They would tell me, ‘Mike, it’s no big deal, you just got dinged on the head.’ They minimized it. When you call something as serious as a concussion just ‘getting dinged on the head,’ you train the players to perceive it as just a minor thing.”

“Whenever I had a concussion, I would end up crying like a baby. Typically I would black out for about fifteen minutes and then wake up crying on the bench. One time, I threw a twenty-yard pass completion while I was blacked out, and in a film study session later that week, I was watching a ten-play drive of which I had absolutely no recollection—no memory of it at all.”

While concussions are a term understood by many, medical discourse on the NFL has drifted away from the subject of concussions in recent years. Instead, sub-concussive hits, or small, repeated blows to the head, have become the subject of increasing attention because of the damning evidence being uncovered in the brains of former football players.

These repetitive sub-concussive hits—the ones that a linebacker might experience on each one of his 100-plus tackles in a season—have been described as the building blocks of a neurodegenerative disease known as Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE).

Linked to depression and dementia, CTE is characterized by a buildup of tau, an abnormal protein that destroys neurons in areas of the brain controlling emotions, memory, and other functions. Autopsies of more than 50 ex-NFL players, including Hall-of-Fame center Mike Webster and All-Pro linebacker Junior Seau, found tau concentrations associated with CTE.

CTE has rapidly gained publicity in recent years after it was discovered in the brains of Seau, Pro Bowl safety Dave Duerson, and safety Ray Easterling, all of whom were former players who reportedly exhibited eccentric behavior before committing suicide.

Boryla laments the ravages of CTE, especially after receiving snaps from Webster in the 1975 Pro Bowl only to see his football friend die at the young age of 50.

“On an episode of Frontline, they estimated that Webster suffered the equivalent of 1,000 car accidents during his career. It was so hard for me to watch that episode,” Boryla revealed.

Fortunately for Boryla, he believes he suffered no more than one sub-concussive blow in his career, a fact about which he is fairly certain because he knows the distinct feeling of experiencing one.

“I was a wide receiver during my freshman year at Stanford playing in a game against USC. The play had stopped, so I had just kind of relaxed, but the opposing cornerback just took his elbow and hit me right underneath my chin. My head bounced back, and I saw stars, just like in the cartoons. It took about three or four seconds to get back in the play.”

“And I was on the field for the next play. That is the danger of sub-concussive hits: the players continue playing. On the other hand, if you suffer a concussion, you are out for 15 minutes, and you wake up lying on the bench and cannot go back into the game. They also say that the danger of sub-concussive blows is that the players just get used to seeing those stars, experiencing that blurry vision, and feeling disoriented for about five seconds. Then they move back into focus and go back and play. I did not miss a play when I experienced that one sub-concussive blow.”

Experiencing a modest total of three concussions and one sub-concussive hit, Boryla left the NFL relatively unscathed, which he attributes to his decision to walk away prematurely.

“Former players look and walk like old men. They all walk away with memory problems,” he says. Boryla, on the other hand, is enjoying good health and has crafted a successful post-NFL career that has included working as a lawyer, as a mortgage banker, and now as a playwright.

Boryla simply did not see the value in sacrificing his future health to continue playing football.

“The average NFL career is only three-and-a-half years, and those three-and-a-half years shave close to 20 years off a player’s lifespan. Just think about that: you spend three-and-a-half years playing NFL football, and your lifespan is reduced by close to 20 years. One year in the NFL cuts your lifespan by about seven years. It is amazing.”

Before becoming a full-time playwright, Boryla worked as an attorney for 20 years. As such, he has a unique perspective on legislation targeted against football.

For one, he feels that his career in law has engendered in him a sense of pragmatism. For this reason, he does not see the NFL being banned in the near future—or even during his lifetime.

“As far as whether NFL football should be banned, I am a lawyer, so I do not engage in fantasy thinking. There 84 million fans, and the NFL made $9 billion last year. I am not stupid enough to imagine a world in which we can ban an enterprise that earns $9 billion a year.”

Instead of spending his time dreaming up fantasies, Boryla has spent some of it working with Michael Benedetto, Member of the New York State Assembly. In fact, he says he encouraged Benedetto to introduce legislation to ban football under the age of 13.

Such a ban would agree with the opinions of a growing number of Americans, who are more aware than ever of the dangers the sport poses to children. According to a poll from Robert Morris University, more than 40 percent of the individuals surveyed argue that elementary, middle, and junior high school students should be barred from participating in football.

However, Boryla believes the court of law already has the perfect strategy in place to fight the dangers of football. He points to the huge class-action lawsuit against the NFL led by over 4,800 retired players suffering from concussion-related effects, hoping that they refuse a settlement.

“I do not want the case to be settled. I want them to go to the discovery phase, and I want them to find the smoking guns—and I strongly believe that they are there—that show that the NFL knew about the effects of concussions and hid them from its players.”

“When I was an attorney, whenever our group wanted to hammer the other party, we would always try to make Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) complaint. A RICO complaint allows you to get triple damages as well as punitive damages. If the players refuse to agree to the settlement, I believe the NFL’s smoking guns will come to light, and then players can get the punitive damage award and decimate the league financially.”

If instead the players agree to the $765 million settlement, then Boryla acknowledges that the country must wait for public perception to turn against football, possibly from sources such as media, before any laws can be passed to ban the sport among children or to discard it altogether.

“Here’s what I think is going to happen. Ridley Scott, one of the top movie directors in the world, once made the movie Gladiator, one of the best movies I have ever seen. He is making a movie on concussions in the NFL that he announced recently.”

Boryla is referring to Scott’s as-yet-untitled drama film focusing on the NFL’s complicity in allowing its players to suffer the effects of concussions. Scott plans to create a morality tale on this hot-button issue, akin to Michael Mann’s 15-year-old film The Insider, which exposed the tobacco industry’s efforts to conceal the addictive and carcinogenic effects of cigarette smoking.

“I think when that movie comes out, and even if it is half as good as Gladiator, you will a shift in public perception against football, and then I can see some of these bills gaining traction.”

As Scott prepares his movie, Boryla is at work conveying a similar message in his play.

“Since I am really the first person to become a playwright-football player, I feel as though I have a responsibility to represent the players and talk about some of these issues.”

"The Disappearing Quarterback" runs through February 2 in a production by Plays & Players at the third-floor studio of Plays & Players Theatre, Delancey Place between 17th and 18th Streets. For more information, call 866-811-4111 or visit www.playsandplayers.org.

As I walk into Philadelphia’s Plays & Players Theatre on a snowy January afternoon, I watch Mike Boryla on stage as he portrays his experience of a concussion during a rehearsal for his one-man play, The Disappearing Quarterback.

“Wow, who are these people?” he asks, with a look of befuddlement plastered on his face. “Why are they looking at me? They all look so nervous and worried. Why are you shining that light in my eyes? It’s so bright. And what kind of building is this? There’s no roof on it. Why not?”

“Name? What’s a name? What are you talking about?”

“Why am I crying so hard? What am I doing here? Where am I? Who am I?”

In his play premiering on January 23, Boryla has a story to tell—a story about what professional football does to its players, and what happens to them after they retire.

A standout player at Stanford, Boryla replaced Roman Gabriel as the Eagles quarterback in 1975 before giving way to Ron Jaworski and ultimately to a series of concussions. He retired at the height of his career, making the decision to walk away primarily because of his fears about concussions.

In fact, during his five years in the league, Boryla grew progressively irked by the NFL culture that treated concussions as harmless injuries.

“They would tell me, ‘Mike, it’s no big deal, you just got dinged on the head.’ They minimized it. When you call something as serious as a concussion just ‘getting dinged on the head,’ you train the players to perceive it as just a minor thing.”

“Whenever I had a concussion, I would end up crying like a baby. Typically I would black out for about fifteen minutes and then wake up crying on the bench. One time, I threw a twenty-yard pass completion while I was blacked out, and in a film study session later that week, I was watching a ten-play drive of which I had absolutely no recollection—no memory of it at all.”

While concussions are a term understood by many, medical discourse on the NFL has drifted away from the subject of concussions in recent years. Instead, sub-concussive hits, or small, repeated blows to the head, have become the subject of increasing attention because of the damning evidence being uncovered in the brains of former football players.

These repetitive sub-concussive hits—the ones that a linebacker might experience on each one of his 100-plus tackles in a season—have been described as the building blocks of a neurodegenerative disease known as Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE).

Linked to depression and dementia, CTE is characterized by a buildup of tau, an abnormal protein that destroys neurons in areas of the brain controlling emotions, memory, and other functions. Autopsies of more than 50 ex-NFL players, including Hall-of-Fame center Mike Webster and All-Pro linebacker Junior Seau, found tau concentrations associated with CTE.

CTE has rapidly gained publicity in recent years after it was discovered in the brains of Seau, Pro Bowl safety Dave Duerson, and safety Ray Easterling, all of whom were former players who reportedly exhibited eccentric behavior before committing suicide.

Boryla laments the ravages of CTE, especially after receiving snaps from Webster in the 1975 Pro Bowl only to see his football friend die at the young age of 50.

“On an episode of Frontline, they estimated that Webster suffered the equivalent of 1,000 car accidents during his career. It was so hard for me to watch that episode,” Boryla revealed.

Fortunately for Boryla, he believes he suffered no more than one sub-concussive blow in his career, a fact about which he is fairly certain because he knows the distinct feeling of experiencing one.

“I was a wide receiver during my freshman year at Stanford playing in a game against USC. The play had stopped, so I had just kind of relaxed, but the opposing cornerback just took his elbow and hit me right underneath my chin. My head bounced back, and I saw stars, just like in the cartoons. It took about three or four seconds to get back in the play.”

“And I was on the field for the next play. That is the danger of sub-concussive hits: the players continue playing. On the other hand, if you suffer a concussion, you are out for 15 minutes, and you wake up lying on the bench and cannot go back into the game. They also say that the danger of sub-concussive blows is that the players just get used to seeing those stars, experiencing that blurry vision, and feeling disoriented for about five seconds. Then they move back into focus and go back and play. I did not miss a play when I experienced that one sub-concussive blow.”

Experiencing a modest total of three concussions and one sub-concussive hit, Boryla left the NFL relatively unscathed, which he attributes to his decision to walk away prematurely.

“Former players look and walk like old men. They all walk away with memory problems,” he says. Boryla, on the other hand, is enjoying good health and has crafted a successful post-NFL career that has included working as a lawyer, as a mortgage banker, and now as a playwright.

Boryla simply did not see the value in sacrificing his future health to continue playing football.

“The average NFL career is only three-and-a-half years, and those three-and-a-half years shave close to 20 years off a player’s lifespan. Just think about that: you spend three-and-a-half years playing NFL football, and your lifespan is reduced by close to 20 years. One year in the NFL cuts your lifespan by about seven years. It is amazing.”

Before becoming a full-time playwright, Boryla worked as an attorney for 20 years. As such, he has a unique perspective on legislation targeted against football.

For one, he feels that his career in law has engendered in him a sense of pragmatism. For this reason, he does not see the NFL being banned in the near future—or even during his lifetime.

“As far as whether NFL football should be banned, I am a lawyer, so I do not engage in fantasy thinking. There 84 million fans, and the NFL made $9 billion last year. I am not stupid enough to imagine a world in which we can ban an enterprise that earns $9 billion a year.”

Instead of spending his time dreaming up fantasies, Boryla has spent some of it working with Michael Benedetto, Member of the New York State Assembly. In fact, he says he encouraged Benedetto to introduce legislation to ban football under the age of 13.

Such a ban would agree with the opinions of a growing number of Americans, who are more aware than ever of the dangers the sport poses to children. According to a poll from Robert Morris University, more than 40 percent of the individuals surveyed argue that elementary, middle, and junior high school students should be barred from participating in football.

However, Boryla believes the court of law already has the perfect strategy in place to fight the dangers of football. He points to the huge class-action lawsuit against the NFL led by over 4,800 retired players suffering from concussion-related effects, hoping that they refuse a settlement.

“I do not want the case to be settled. I want them to go to the discovery phase, and I want them to find the smoking guns—and I strongly believe that they are there—that show that the NFL knew about the effects of concussions and hid them from its players.”

“When I was an attorney, whenever our group wanted to hammer the other party, we would always try to make Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) complaint. A RICO complaint allows you to get triple damages as well as punitive damages. If the players refuse to agree to the settlement, I believe the NFL’s smoking guns will come to light, and then players can get the punitive damage award and decimate the league financially.”

If instead the players agree to the $765 million settlement, then Boryla acknowledges that the country must wait for public perception to turn against football, possibly from sources such as media, before any laws can be passed to ban the sport among children or to discard it altogether.

“Here’s what I think is going to happen. Ridley Scott, one of the top movie directors in the world, once made the movie Gladiator, one of the best movies I have ever seen. He is making a movie on concussions in the NFL that he announced recently.”

Boryla is referring to Scott’s as-yet-untitled drama film focusing on the NFL’s complicity in allowing its players to suffer the effects of concussions. Scott plans to create a morality tale on this hot-button issue, akin to Michael Mann’s 15-year-old film The Insider, which exposed the tobacco industry’s efforts to conceal the addictive and carcinogenic effects of cigarette smoking.

“I think when that movie comes out, and even if it is half as good as Gladiator, you will a shift in public perception against football, and then I can see some of these bills gaining traction.”

As Scott prepares his movie, Boryla is at work conveying a similar message in his play.

“Since I am really the first person to become a playwright-football player, I feel as though I have a responsibility to represent the players and talk about some of these issues.”

"The Disappearing Quarterback" runs through February 2 in a production by Plays & Players at the third-floor studio of Plays & Players Theatre, Delancey Place between 17th and 18th Streets. For more information, call 866-811-4111 or visit www.playsandplayers.org.